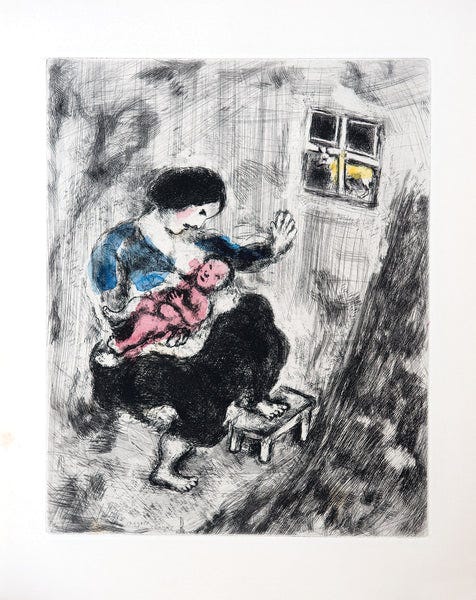

The Wolf, the Mother, and the Child (Marc Chagall, 1952).

At a recent Upstate New York agricultural fair, I met an old man demonstrating traditional Native crafts. He was a member of the Big Horn Lenape tribe, a nation unrecognized by the U.S. government, whose ancestral bloodlines are significantly mixed with those of other ethnic groups; he was also an authority on the language and culture of the Delaware, was the author of several books on the subject, and had ample documentation of his people’s journeying and settlement history. I concluded that the question of “Who is an Indian?” is perhaps as vexed as the age-old one “Who is a Jew?”

Members of the non-federally-recognized Big Horn Lenape and Eastern Delaware Nations at a Powwow.

My conversation with this elder raised questions about the modern world’s simultaneous hardening and loosening of identity. On the one hand, the institutions of law and scholarship declare that identity is materially fixed in the individual — that one can never, for example, leave behind one’s blackness or whiteness — while at the same time that its attributes go beyond individual phenotype, to morph into a kind of miasm that controls social behavior en masse. On the other hand, for instance when it comes to gender, the same institutions assert that scientifically-observable biological dimorphism can fade, crumble, and disappear if one believes that it can.

As with social beliefs about racial and ethnic phenotypes, beliefs about gender identity go beyond the individual, expressing themselves in a social corollary that assigns to them an absolute moral value. In a much commented-upon recent discussion between Ezra Klein and Ta-Nehisi Coates, for example, the former opined (video cued to statement):

A huge amount of the country, a majority of the country, believes things about trans people . . . that we would see as fundamentally and morally wrong.

These morally wrong beliefs include questioning whether minor children should be medicalized to more convincingly appear as the opposite gender; whether trans women with the augmented strength and size conferred by male puberty should compete in women’s sports; and whether biological males identifying as females should have access to sex-segregated spaces like women’s locker rooms and domestic violence shelters. Klein and Coates, although they differ on the main topic of the discussion in question — Charlie Kirk — make up the “we” to whom Klein refers, united in aligning themselves with absolute good against the fundamentally morally wrong majority of the country.

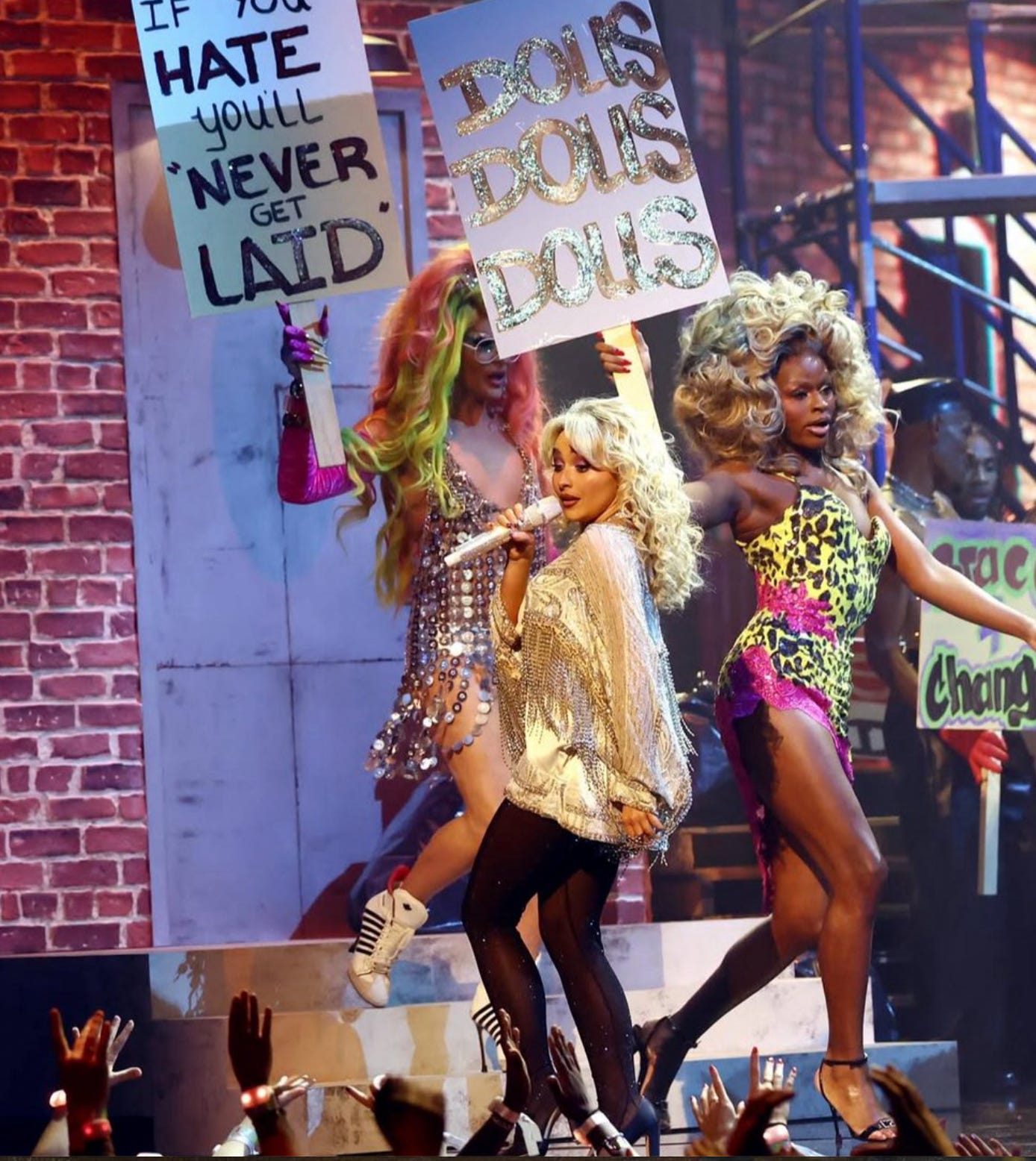

Sabrina Carpenter performing with drag queens at the MTV Video Music Awards in September: the sign on the left is a reference to Carpenter’s song “Never Getting Laid”; the “Dolls, Dolls, Dolls” sign evokes a popular term for trans women.

All of this brings me back to my talk with the Big Horn Lenape elder. I think that perhaps the foundational struggle in every life is the question: Who am I? And, vis-à-vis the elder’s tribal affiliation, the related question: To what extent does one’s ancestry matter?

Several years ago, when Senator Elizabeth Warren sought to validate her self-identification as Cherokee with a DNA test that showed a Native American ancestor some ten generations back, she was roundly chastised by Cherokee Nation Secretary of State Chuck Hoskin, Jr., who said, “Using a DNA test to lay claim to any connection to the Cherokee Nation or any tribal nation, even vaguely, is inappropriate and wrong.” So Cherokee-ness is defined not by the individual who self-identifies as such, but rather by the collective that has reached consensus on the terms and regulations that legitimize this identification. Very different from the increasingly accepted definition of womanhood as “someone who identifies as a woman.”

And it may be that choosing one’s own identity is a statement of opposition to womanhood itself in a fundamental way — specifically of opposition to the Mother. When we create our own identity, we both unravel the past and shelve the collective memory of the tribe; in short, we jettison the Mother.

When my forebears arrived in New York as refugees from Belarus, they were profoundly changed not only by becoming Americans, but by the act of moving off the land. In Vitebsk, my great-grandfather was a woodturner; in New York, he sold consumer goods off a pushcart in the ghetto. There was a distinct process of deskilling that accompanied resettlement: now, three generations into the project of Americanization — which walks hand in hand with urbanization — it pains me to take stock of my own paltry skills.

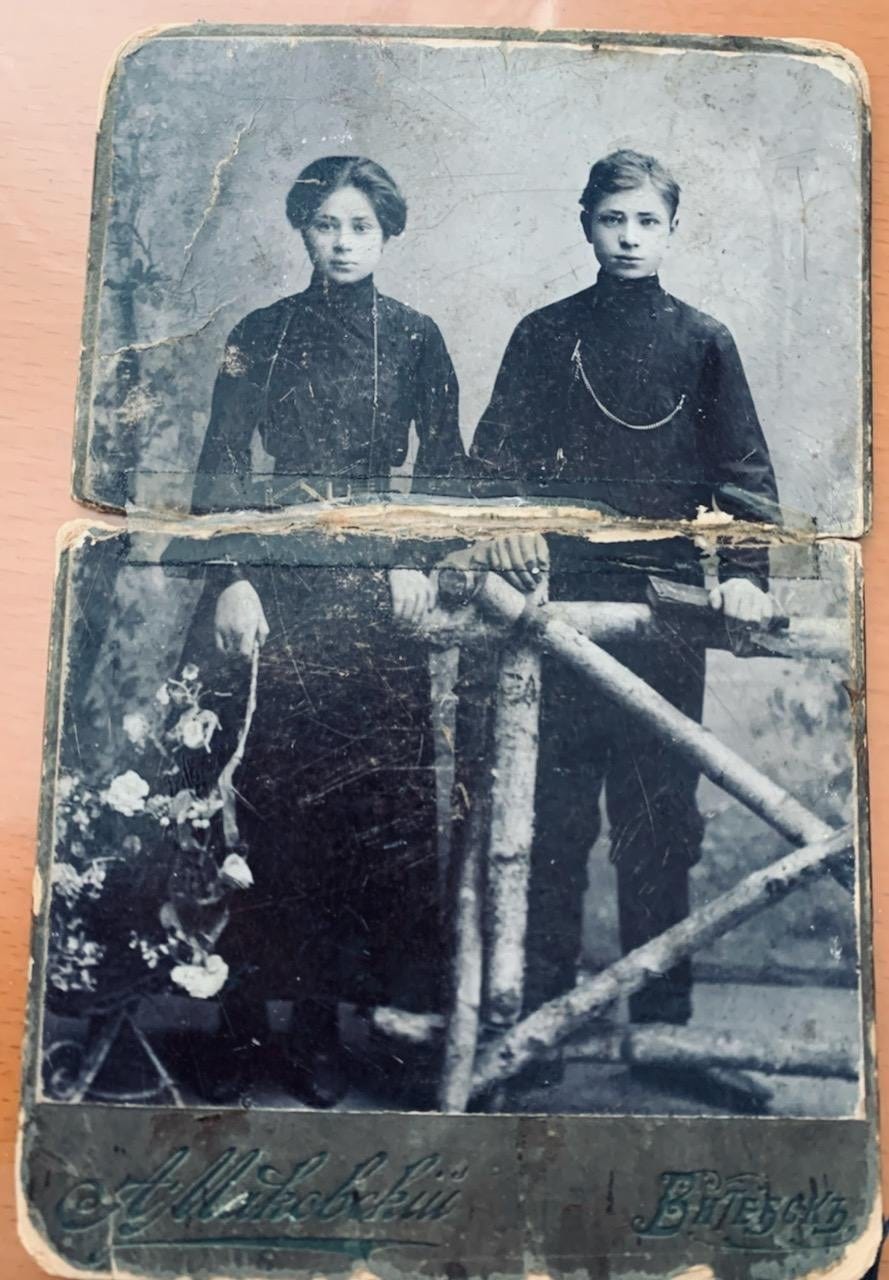

My great-grand-aunt Miriam Raskin and her brother Yosyp in Belarus.

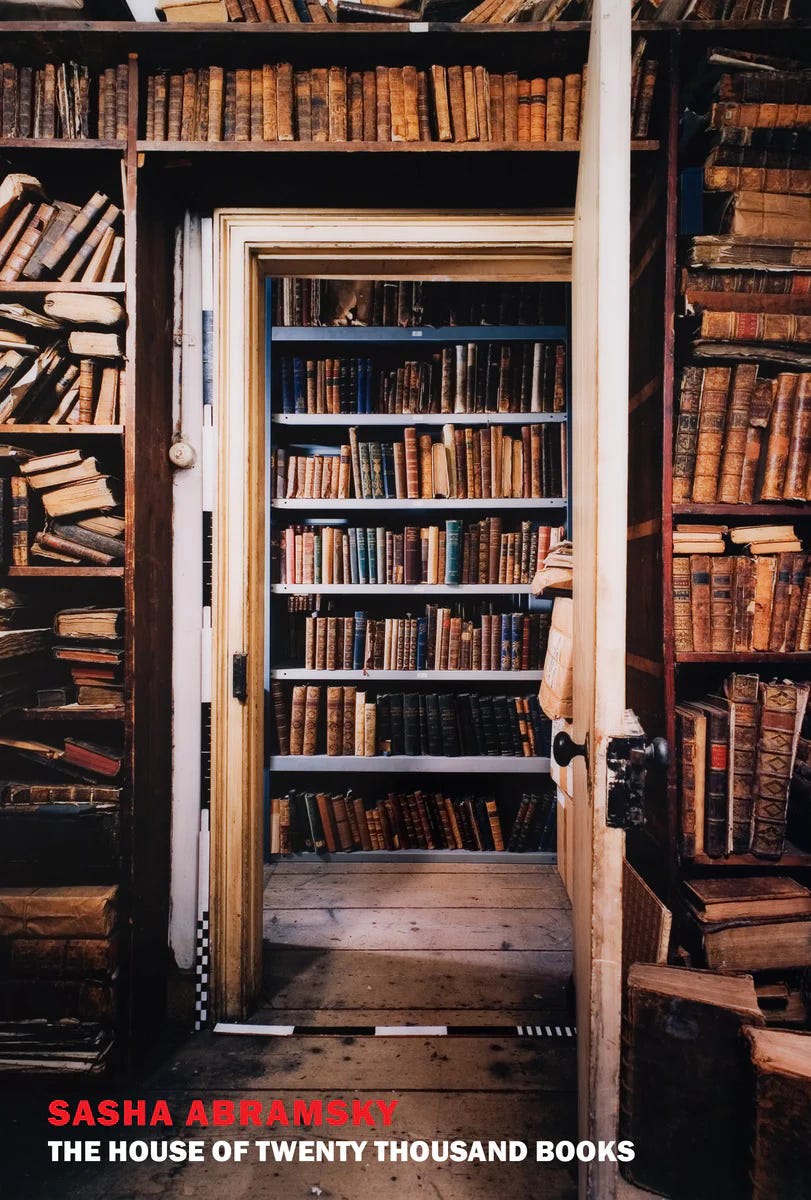

I recently read a captivating memoir, The House of 20,000 Books by Sasha Abramksy, an intellectual biography of his grandfather Chimen Abramsky, a British Jewish bibliophile and polymath. Chimen’s family also fled Belarus after his father Yehezkel, a respected rabbi, was sentenced to death for counterrevolutionary activities (in this case, holding to his faith). Yehezkel’s sentence was commuted to five years in a Siberian labor camp, after which he came with his family to England, where his son Chimen became an eminent propagandist for the British Communist Party.

Chimen believed that his father’s sentence was well deserved for having opposed the liberatory project of Stalinism. A drawback of Sasha Abramsky’s biography is that he doesn’t fully explain his grandfather’s belated apostasy from communism in 1958. I find it relatively easy to excuse American (or English) Communists who, on the rare chance that they may have had to view Soviet Communism up close, saw Potemkin Villages. It’s less so to apprehend the almost Oedipal accusations against his own father of a brilliant young man like Chimen Abramsky.

In the end, however, I wonder how much of radical politics springs fully-formed and -armed from psychic wounds. In the case of my own Communist grandmother Josephine Nordstrand, the mother-wound is hinted at in the stories of her sister Iris (née Faigele), who later recalled, in a document transcribed by her daughter Me’irah:

My mother [my own great-grandmother Rose Apartzova, who emigrated to America in 1905 — Julia] was supposed to marry a rabbinical student, but they were reduced to poverty overnight. She had to work, lost her dowry, he wouldn’t marry her. She wasn’t happy with my father [woodturner Abraham Raskin]. In America she met an exciting man who was a union organizer. He was amenable to taking my sister [my grandmother Josephine — Julia] with him, but when he found out she was pregnant with me, he walked out on her. [My mother Rose] would say to me, “if it wasn’t for you, my life would be better.” Mother had tantrums, [would] pull out drawers and dump them on the floor, and cry all day.

My great-grandmother Rose Apartzova Raskin came to live with my family as a very old woman when I was a very young child. Grandma Rose, as we called her, was a living link to the Old World. She was born in the shtetl outside of Vitebsk (also Marc Chagall’s hometown), and came over on the RMS Teutonic out of Liverpool as an 18-year-old fleeing a pogrom after a punishing land trek across Europe. Her first language was Yiddish, fondly known as the “Mamaloshen” — the mother-tongue — implying not only a native language, but also a sense of profound nurture and rootedness. For all of that, though, it seems as if Grandma Rose was unable to provide this nurture to her own children, two out of three of whom grew up to join the Communist Party.

Communism, however, was itself a fickle mother, and left still more unmothered children in its wake, including my own mother, whom my grandmother Josephine abandoned for the Revolution.

And amidst these ruminations I think of my own youngest child, who was found as a newborn by the side of the road on a busy highway in a Communist country, an unmothered child cast out by Communism, who no longer knows his own mother-tongue.

My grandmother Josephine Nordstrand (née Esther Raskin), left and her sister Iris Merrick (née Faigele Raskin), Brooklyn, NY, c. 1915.

I have no answers for these vexing questions. But I believe deep in my bones that to be human means abandoning revolution for the painstaking, frustrating work of binding up the wounds, however clumsily, of those who appear in front of us.

Thank you Lady Mary! I'm trying to understand things that realistically I may never.

Thank you, Julia! I remember reading Coates’ article in The Atlantic justifying reparations. I lost a close friend over that article because I said that, although the article was well-written, it didn’t make a very coherent argument. Now, I’m not sure what I thought was so good about his writing.