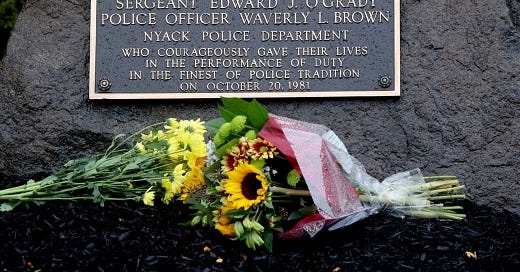

Memorial to the officers slain in the 1981 Brinks robbery, Nyack, NY

The other day I drove a fairly long distance to my old homeplace, New York City, to say farewell to a lifelong friend moving to the west coast. I used to think of the city as a kind of palimpsest for my life and millions of others, but now it’s just a place churning with its own meaning…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Teach Like A Mother to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.